The Beginning Knowledge Book of Backyard Birds

The Beginning Knowledge Book of Backyard Birds was a nice find for $1 at my local library’s sale rack. I was drawn to its cover which features a family of Red-headed Woodpeckers, a Connecticut species I am fond of and one that sparks nostalgia in me. I have not seen one in person since I was a child and these days if anyone ever tells me they spotted one it always turns out to be the ubiquitous Red-bellied Woodpecker — 100% of the time. According to the Connecticut Audubon Society, Red-headed Woodpecker populations have gone down 70% in the past 50 years due to habitat loss — hastening a decline that began with the chestnut blight of the early 1900’s which wiped out a significant part of their food supply. The chestnut blight entered the Eastern US from Japan on nursery plants that were delivered to the Bronx Zoo in 1904, making it a human-facilitated invasive pathogen that species like this woodpecker were not equipped to deal with. This woodpecker has lost a lot of ground here in New England due to the interference of humans through trade and land development, and unlike their more urbanized relatives the Downies and Red-Bellies it seems that they must thrive in areas of lower impact and perhaps do not share the same fondness for feeders. Looking back at my old neighborhood I remember it through child’s eyes as a woodland wonderland, but when I last drove down our street I saw that a large swath of land that was once tangled and wild has been cleared to make room for open lawns and bland, hulking houses. Fortunately the Red-headed Woodpecker has received attention and conservation efforts and there are more stable populations elsewhere, but in Connecticut they remain on the state endangered species list.

I confess I did not crack open this book more than once or twice since purchasing it — beyond the cover it did not really call out to me and the illustrations fell kind of flat. Upon opening it again to start this blog entry I was surprised to see that Guy Coheleach was the illustrator; apparently I hadn’t even bothered to look at the byline when I first picked it up, I might’ve given it more attention if I was aware of the name on it. Coheleach is a famous wildlife artist and is especially well-known for his paintings of African animals and big cats. This book’s publication date in 1964 sets us well back into Coheleach’s early career at age 31, two years before his first trip to Africa. This information reframed my experience of the artwork in this book — I’m making some assumptions but my impression of his work in this book has the feeling of one of those projects we take when we are still “figuring things out” as artists. Coheleach grew into a true master and still going strong at 86 years old, don’t give up if you are going through those searching years yourself as it can be the beginning of great things.

Here is another book with fully illustrated endpages and these feature a very simplified anatomical diagram of a robin bringing a twig to a nest. This fellow, as with some other birds in the book, is suffering from “Egyptian perspective” — head and feet are flattened in profile while the rest of the body and torso are askew. I’m not bringing this up to roast our (beloved) artist, it’s a widespread and tempting mistake for all bird illustrators at any level that I thought would be worth noting — for what better way is there to show our viewer as much structural information as possible than to pull all the pieces out of hiding and into clear view? This piece is a good example of what can go wrong if we fall into this habit. Not only do we trade the bird’s natural posture and movement for flat rigidity (“fly like an Egyptian”), we end up painting ourselves into a corner as there is always a structure that won’t fall in line. In this illustration it is the open wing being forced into extreme foreshortening — the information about this structure has been entirely sacrificed for the sake of putting everything else on display and gives us an awkward end result. This is one reason why most anatomical diagrams do not make an effort to double up as an illustration about behavior activity, and why bird diagrams favor the use of multiple angles instead of trying to cover everything in one view (Sibley’s are excellent examples of this).

Another Egyptian Perspective bird here — in this example the foreshortening of the nearest wing and the tail are well-executed and it’s now the legs that get pulled into distorted, confusing perspective.

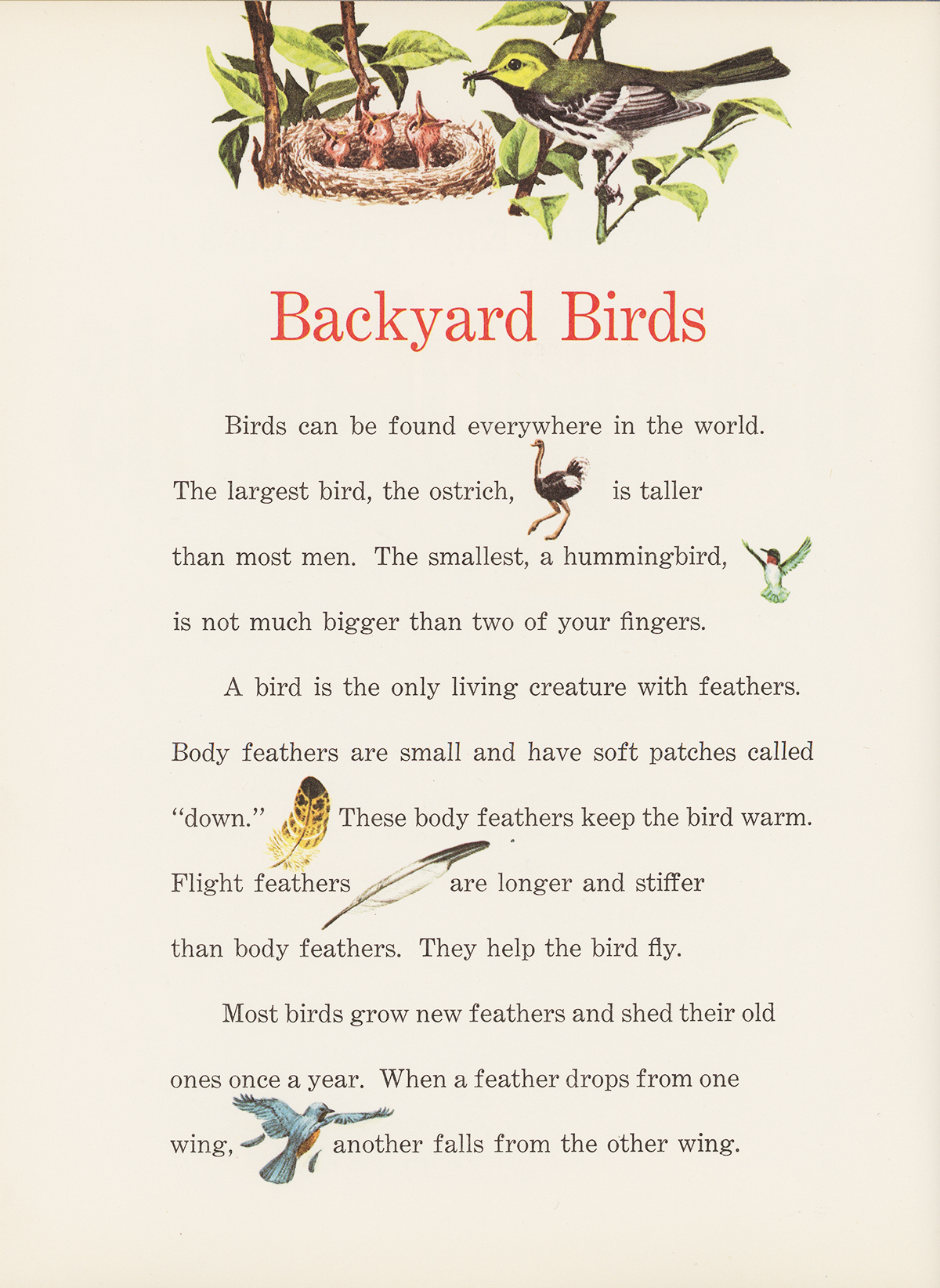

My favorite pages of this book are actually the simplest ones: just a handful of introductory pages featuring tiny paintings embedded in each line of text. It’s very appealing and cute, it brings to mind a heart-warming image of a parent reading to a child as their finger traces the lines of text so that when they read the name of each bird they skim along the corresponding image. It makes the book more interactive and valuable to very young readers. I remember seeing pages like these when I was a kid but I have to admit that looking at them now they are rather like our modern emoji. 1964 meets 2019.

The Northern Flicker and Evening Grosbeak have my favorite full page illustrations. The rendering on this Flicker’s body and the full use of the page in its composition make this one impactful to my eye. The grosbeaks are very informative with a food source present and our female in a much more successful pose than the earlier pages I posted. The feather detail and depth on the flicker are very inspiring, this is an ornate and difficult species to illustrate and the detail of these stacked patterned feathers is very lovely — his body is the most richly defined form in the book, in my opinion. I also like the little offshoot of the tree, the light hits it very nicely and it informs the viewer that this is a dead snag which gently provides more natural history information about the subject.

Most of the graphite drawings accompanying the non-color pages are not as appealing to me and feel a bit lost, several of them are a bit disproportionate or dreary. Frankly it’s a little reassuring to see a few frumpy birds in the history of such a standout artist, since I have many frumpy birds of my own under my belt. In the end this is a sweet little book and I am glad to have spent more time with it.